In Serbia, Veliki Petak (Good Friday) is more than a religious observance—it is a deeply spiritual and emotional day marked by quiet reflection, rich symbolism, and centuries-old traditions. It is observed on the Friday before Easter Sunday, commemorating the crucifixion of Jesus Christ and his death at Calvary.

As a predominantly Orthodox Christian country, Serbia observes Veliki Petak with solemnity, reverence, and a tapestry of customs that blend faith, folklore, and family. From silent mourning to the coloring of Easter eggs, this day sets the tone for the most important holiday in the Christian calendar—Vaskrs (Easter).

The Meaning of Veliki Petak

Veliki Petak is the most sorrowful day of Velika Nedelja (Holy Week), the period leading up to Orthodox Easter. It symbolizes the ultimate sacrifice of Jesus, who was crucified to redeem humanity’s sins.

In the Orthodox Church, this day is observed with strict fasting, prayer, and attendance at special church services that recall the Passion of Christ.

Traditions and Customs in Serbia

1. Strict Fasting and Silence

Most devout Serbs do not eat or drink until sunset on Veliki Petak. When they do eat, the food is typically simple—without oil, meat, dairy, or alcohol. Some even avoid cooking altogether.

This fasting is a way of cleansing the body and spirit, honoring the suffering of Christ.

Interesting fact: In rural areas, it’s not uncommon for families to avoid any housework or loud activities on this day. Some believe that working on Veliki Petak brings bad luck.

2. Church Services and Lamentations

On Veliki Petak, Serbian Orthodox churches are filled with worshippers attending special services, including the reading of the Twelve Gospels, which narrate the events leading to the crucifixion.

Later in the evening, a symbolic burial service of Christ is held, where believers pass under a table covered with a shroud (called plaštanica) that represents Jesus’s tomb. Walking under the table is believed to bring spiritual blessings and protection.

3. Coloring Easter Eggs

Although Easter egg dyeing is mostly associated with Holy Saturday, many households in Serbia begin this ritual on Veliki Petak—particularly the dyeing of the first red egg, known as the čuvarkuća (“guardian of the house”).

This red egg symbolizes Christ’s blood and is kept in the home throughout the year for protection.

Interesting fact: In some villages, people still use natural dyes, such as onion peels, beetroot, or herbs, to color eggs the traditional way.

4. No Music, No Celebrations

Unlike many Western countries where Good Friday might pass with little outward notice, in Serbia, Veliki Petak is a day of silence. There is no music, no dancing, and no celebrations. Radios and TV programs also avoid cheerful content, focusing instead on religious or neutral themes.

5. Folk Beliefs and Superstitions

Serbian folklore is rich with beliefs tied to this day. Some people believe that rain on Veliki Petak is a sign of blessing, while others think that whatever you do today will follow you all year, encouraging people to act mindfully and prayerfully.

A Day Between Sorrow and Hope

Veliki Petak is not just a day of mourning—it’s also a day of hope and renewal, bridging the sorrow of the crucifixion with the joy of resurrection. It is a day when churches are filled with candlelight, when homes are quiet in reflection, and when the red egg—a symbol of life emerging from death—holds deep significance.

How to Experience Veliki Petak in Serbia

If you’re in Serbia during Holy Week, visiting a local church on Veliki Petak offers a powerful glimpse into Serbian spirituality. Whether in a village or a Belgrade cathedral, you’ll witness a blend of ancient Orthodox ritual and heartfelt community devotion.

Be respectful of the silence, avoid festive clothing or loud conversation, and if you’re lucky, you might be invited to join in the egg dyeing or fasting meal.

Veliki Petak in Serbia is a profound cultural and spiritual event—a day when the country collectively slows down, reflects, and prepares for the glory of Easter. It’s a time when faith and folklore intertwine, reminding us of the enduring power of tradition, sacrifice, and renewal.

Related Articles

5 Little Things in Serbia That Travelers Never Forget

February 20, 2026

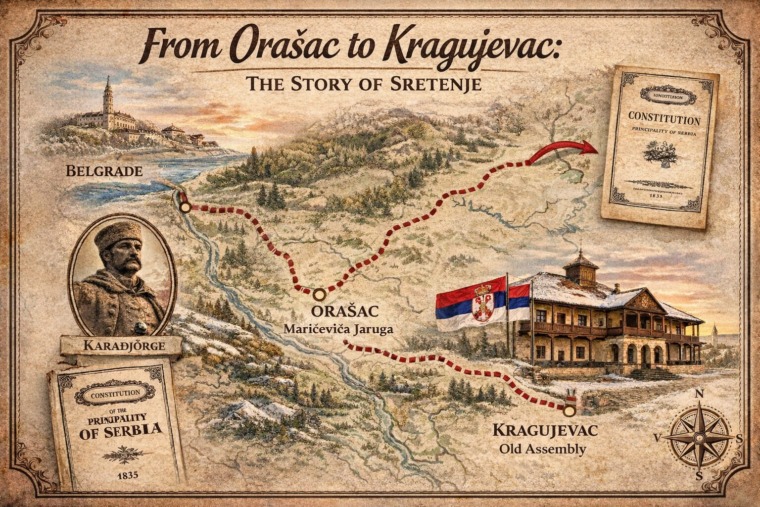

Interesting Facts About Sretenje You May Not Know

February 16, 2026