“Highlanders with innate manners, shepherds who live for freedom and women as beautiful as ladies from Swiss cantons” – this is how Alphonse de Lamartine, a French romanticist, poet, writer and politician saw the people of Serbia during his visit in 1833.

Was Alphonse de Lamartine actually the one who has established the French-Serbian friendship, and not World War I, as it was considered for a long time?

Lamartine was the first man whose opinion mattered and who spread the word across Europe about sufferings of peoples in the Balkans under the Ottoman ruling and the great courage of Serbs fighting for freedom. Till than his homeland was on good terms with The Ottoman Empire, but it all changed after what Lamartine had to say.

He visited the entire Serbia, met the villagers that hosted him in their modest peasant houses, talked to princes and warriors. Finally Lamartine came to a conclusion that “among them there is very little material inequality, and the only grandeur they have are their weapons” used to defend their freedom.

He liked Serbian language and considered it “harmonious, musical, and rhythmic”. But there is something in the country of this small nation from the Balkans that has deeply touched the heart of this romantic poet.

In July 1833, on his way back from Constantinople he wanted to take some rest not far from the city of Niš. He sat on a rock in front of a structure that he came across and that made a perfect thick shade for a short break to be made there.

When he looked up, he stood horrified. He was facing a frightful tower made of human skulls.

Impressed by the discovery of this barbaric monument, in his book “On Leaving France for the East” in the section “Writings on the Serbs”, Lamartine wrote:

“A path led me towards it; I came closer and after giving a Turkish child who accompanied me to hold my horse, I set in the shades of the tower to take a rest. As I set down, I raised my head and looked at the monument in which shade I was sitting in, and I saw its walls for which it seemed to me to be made of marble or white stone to be actually made of layers of human skulls.

These skulls and those faces pealed and white of rain and sunlight; there could have been fifteen to twenty thousand of it joined with a little bit of plaster, shaping a perfect arch that hid me from the sun; and some of which still had hair fluttering down their necks as some kind of lichen or moss, a strong and fresh breeze blew from the mountains and by blowing through numerous holes on these heads, faces and skulls, created a piteous and sad whistling. There was no one to explain me what this barbaric monument was…”

The poet didn’t have to wait for a long time to find out the explanation. He was roused from this horrifying sight by Turkish horsemen who came to take him to the town and who told him the story of the Battle of Čegar that took place 24 years before Lamartine saw this horrid tower.

He made one last turn and looked at the tower and “with eye and heart greeted the remains of these brave men whose decapitated heads became foundation of their homeland”.

During the First Serbian Uprising against the centuries of Ottoman ruling, this battle was significant for the Serbian Revolutionary Army but it was lost despite the great courage of the Serbian Army led by the famous duke Stevan Sindjelić.

After the Battle, the cruel Hurshid Pasha paid 25 groats for each head of Serbian soldiers in order to fill skinned heads with cotton and send them to Constantinople as a proof of his victory. And as a threat to all Serbs and anyone who would even think of raising another uprising against the great Ottoman Empire he erected a monument made of skulls of 952 Serbian soldiers.

However, nor Serbs nor other Balkan peoples allowed to be frightened so easily, they persisted in their fight, as like Lamartine wrote: “…Serbian people had proud heart that could be torn, but not broken, just like one couldn’t break oak’s heart up in the mountain…”

Related Articles

5 Little Things in Serbia That Travelers Never Forget

February 20, 2026

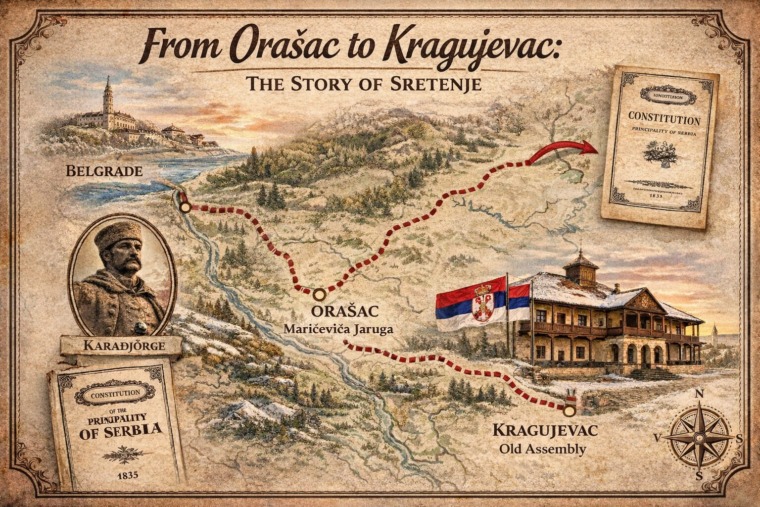

Interesting Facts About Sretenje You May Not Know

February 16, 2026