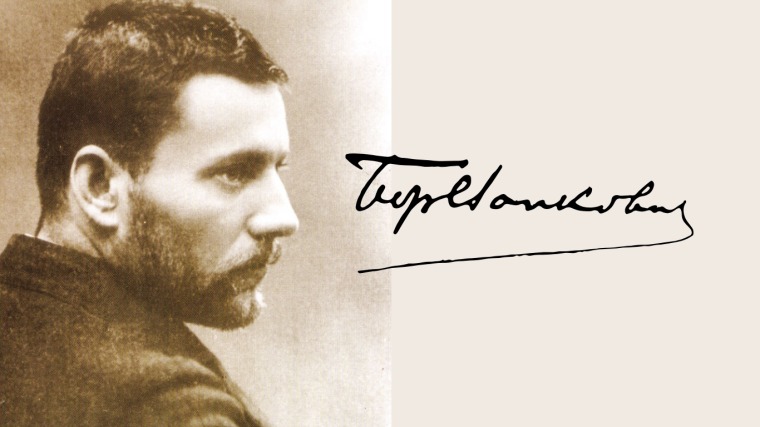

There are people who left their trail imprinted with the printing colour on brittle paper. They are the creatures of arts, the people with gift that only those ready to perfect their mastery get and those trying to elevate life. Their human duration is just a drop in the ocean of eternity; their masterpiece supersedes time and shines like a star even when they cease to exist.

We’ll start the story of Borislav Pekić, one of them, at a Pannonian plain farm, in an attic of his grandmother’s home in the village of Bavanište, at the time when he, as an eleven-year-old researcher discovered a treasure chest. But the treasure that he found in the chest with a rusted frame, a kind of across-the-ocean travel case, is not of ordinary kind. This one included: the dates of birth, marriage and death, joyful and sad events recorded in birth certificates, marriage certificates, records, family documents, and memories: a handful of clippings from newspapers, letters, daguerreotypes, and a gallery of unknown men and women and faraway cities, a whole mysterious world that would spark his imagination. Many years later, he admitted that there, on the lost continent, his Atlantis, he had experienced adventures that would not be surpassed by anything in terms of excitement, and that with the breaking of the case he had started his transgressive career of a novelist. That discovery affected his career more, he wrote, than reading Dostoevsky. As if the spirit of the past was then released, that had seized him and forced him to collect old newspapers, magazines, almanacs, letters, documents, and even receipts and prescriptions, and to make his home a kind of a tomb, where, he didn’t hide that, he felt the liveliest.

THE REBEL WITH A REASON

THE REBEL WITH A REASON

Borislav was born into a middle-class family as the only son of Vojislav and Ljubica Pekić. When the Second World War broke out, his father was the head of the administrative department of the Zeta Province in Cetinje, from where the Italian authorities banished him and his family to Serbia. Mother Ljubica was of Greco-Cincar origin, and before she got married, she taught mathematics. She was a strong and practical woman. She used to say that no one had died from work, and that good upbringing was a universal weapon against all adversities. From her mother, to who he was closer, Borislav inherited rationality and the sense for organisation and from his father high moral principles and the sense of humour.

Since after the war he was not convicted, his father, as an experienced lawyer, received a highly ranked position in the federal administration of the new state in 1945. The Pekić family moved to Belgrade, to Malajnička Street, in Vračar neighbourhood. Borislav enrolled in the Third Men’s Gymnasium. It was as if the moving to Belgrade marked an end to a nice, certain period of his life. It was a much bigger change than just changing the scenery; the end of the war and the victory of the revolution made him aware of the decline of the middle class. “As a member of the class that had the power I felt defeated, dispossessed”, he later said. Already at the age of six, he learned to read from the “Politika” newspapers, and he was “politically” active already as an eight-year-old, and at the age of eleven, as a participant in the demonstrations against the Tripartite Pact, he was detained at his father’s police unit in Cetinje. Already as a high school student he began forming secret organisations that would fight against the new regime. His political maturity will be accelerated by the so-called “high school defascistisation”, a brutal process that he had experienced as an avowed opponent of the new regime in February 1946. He and 42 of his high school fellow students were publicly condemned as opponents of the regime, they went through the crowd of their ravaged peers, who beat them with their hands, sticks, and even chains. This kind of beating-up would later often be practiced on Goli Otok (N.B. an island in the Adriatic Sea where political prisoners were kept at the time of the communist regime in Yugoslavia) and it would get the name “hot rabbit”.

FIRST SCHOOL OF LIFE

Although he did not care much about the real school, he was in circumstances that to a wise man could be the school of life. Pekić himself did not believe in trouble as the sole master of life and inspiration. “Maybe happiness can teach a man something”, he would say.

The first opportunity to gain new experience will follow as a result of illegal anti-regime activities. As a direct response to the “high school defascistisation” the organisation “Union of the Democratic Youth of Yugoslavia” was formed. He was involved in its formation in the summer of 1947, during, lo and behold, the construction of the railway, in a youth work action, a typical model of shaping the collective spirit of the new young generation. As the political secretary of the General Board he wrote the statute of this anti-communist organisation. In youthful enthusiasm, the organisation functioned well; it had a lot of members in all Belgrade gymnasiums as well as in the majority of faculties.

On one November night in 1948, he was arrested and taken to the investigative department of the State Security Service, to the “gloomy house” at Obilićev Venac. That was how “a criminal investigation against Borislav Pekić, an art student and a journalist of Glas, began.” He became one of, as he wrote, “people from the attic”; actually, there were cells there. Pekić would refer to his nearly six-month stay here as his imprisonment “apprenticeship” days.

PRISON CIVILISATION

At the age of eighteen he was sentenced as a serious criminal to “detention and hard labour of 15 (fifteen) years in prison… confiscation of all property and loss of civil rights… for three years…” He spent five years in penal and correctional institutions in Sremska Mitrovica and Niš after having been pardoned. One of the most important things he learned was discovering himself. He wrote: “You learn how fast you are only when you are faced with a tiger; how honourable when you find the money and no one sees you; how sensible when you are asked to do the impossible; whether you are brave only when it is not necessary to be brave; how good only when you are to cope with the evil; and how crazy when you are standing on the bank of the river where a child is drowning, and you can’t swim…” as if this was written by an ancient Chinese wise man and not someone who was doing time in communist jails.

Although he used to say that prisons were to him just a waste of time, the result of his stay in them was not at all insignificant. From a temporal and spatial distance, Borislav Pekić wrote nearly fifteen hundred pages, fictionalised biographies in three volumes “The Years Eaten by the Locusts”. This kind of anthropological study of the so-called prison civilisation, which represents an anatomical cut into the fabric of a time, has put Pekić side by side with Solzhenitsyn, Dostoevsky, Shalamov, among the great writers who, writing about life on the other side of the wall, created masterpieces. Apart from the prison experience, he also earned tuberculosis, from which he had never fully healed.

About what happens later read HERE.

By Jovo Anđić

We thank the Pekić family on conceding the photographs and documents.

Related Articles

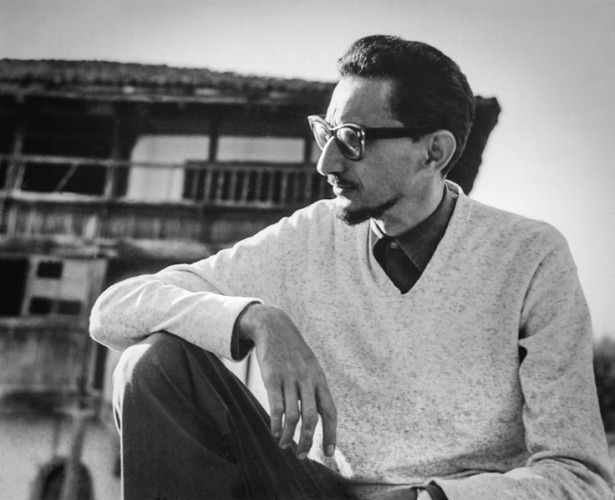

The Father of Serbian Music: Remembering Stevan Mokranjac

September 22, 2025