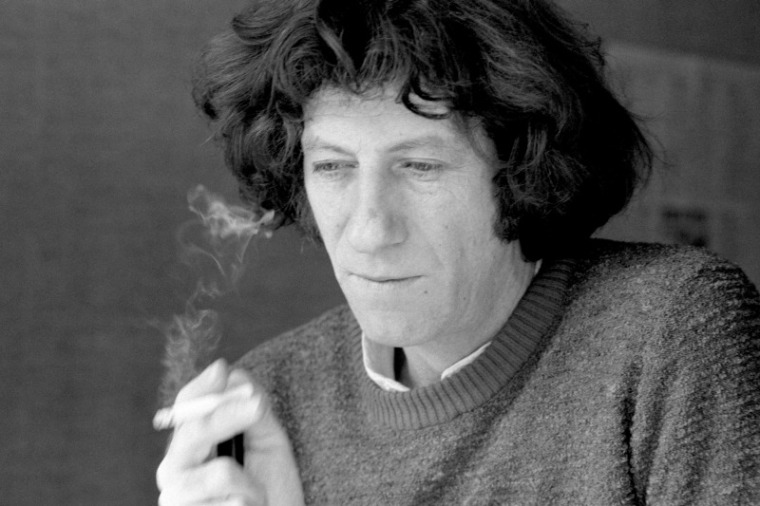

He started writing seriously, as he revealed in one of his interviews, when, as advised by his mother, he started writing a diary, in order to improve his terrible handwriting.

At one point, during the convict days, those diaries grew from a personal confession into a story about others.

He was pardoned on the Republic Day in 1953. Soon after, he began studying experimental psychology at the Faculty of Philosophy and writing screenplays for which he was awarded at anonymous competitions. Then he got married and had a daughter. He dropped out of university and started working in “Lovćen Film” as a dramatist and a screenwriter. He confirmed “his definite commitment to art, literature and public life” with the publication of articles under the pseudonyms in magazines “Vidici” and “Danas”.

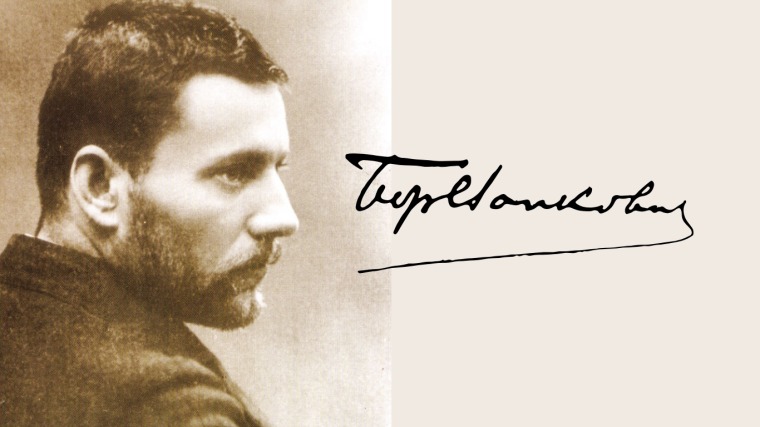

“Borislav, I’ve read the manuscript of ‘The Time of Miracles’, you are a writer,” Borislav Mihajlović Mihiz solemnly told him on the phone. It will be his first published book that came out public in 1965. Mihiz will forever remain Pekić’s first privileged reader and a unique critic, the person whose judgement he trusted the most.

“I used to dream,” Pekić said, “about becoming an explorer of unexamined areas, the discoverer of undefined secrets, a scientist, a traveller towards the stars, an archaeologist, in short, someone who has found something, something particularly important for Mankind (in which I believed then). I became a writer when I realised that I had neither the mental nor physical nor social conditions for all that. But now I regret it.”

LIVING IN A FOREIGN LAND

“I went to a foreign land for two reasons. I felt fallen, sunken, ‘stuck’ in reality deeper than my idea of independence of art allowed… So, I went afar to regain the inner artistic freedom. And even more – my time.” His wife, Ljiljana, an architect, got a job and moved with their daughter, Aleksandra, to London. Bora’s passport was confiscated, and only after nine long months, after winning the NIN Award and after the foreign press wrote about it, his passport was returned to him and he joined his family.

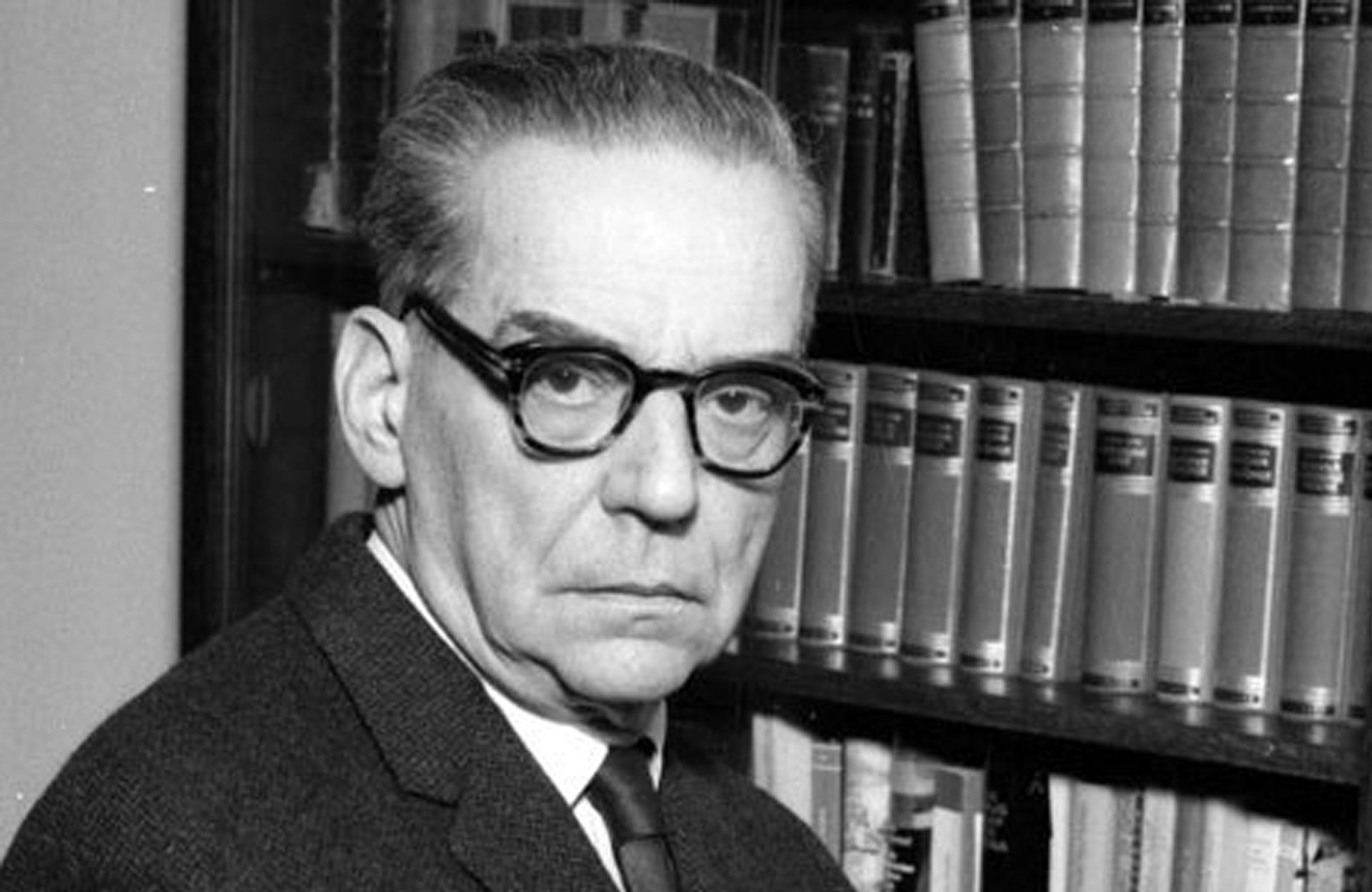

Now he could engage in writing, he had the time, liberty and existential security, provided by his entirely devoted wife. Thousands of pages of novels, plays, screenplays, essays, diary entries emanated from his workshop. He retyped his novelistic cycle “Golden Fleece” of seven books, on three and a half thousand pages, as many as six times on an ordinary machine.

He wrote in “Letters from Abroad”: “the right place is where you grow. Because, of all the lands foreign that the man is convicted to, his own one is still the most tolerable.” He extended his stay in London, originally defined as “some time”, to twenty years.

DEMOCRACY IN ACTION

He was saying that while staying in a foreign country, he learned more about us than about them. He wrote about them and us in “Letters from Abroad”, “A Sentimental History of the British Empire” and he spoke via BBC Radio in London. An exciting time came with the announcement of democratic changes. He was one of the founders of the Democratic Party, a vice-chairman and a participant in the reconstruction of the magazine “Demokratija”. He considered it his duty to help the restoration of democracy. He was a democrat both in the private and public life, aware that democracy was a compromise above all. “…I was brought up as a democrat,” he used to say. “I try to act like a democrat, and to overcome in myself the innate human, totalitarian, I would say, almost anthropological antidemocratic features that originate from selfishness, lust for power, vanity and wicked experience with people. I believe in democracy as the best of all wicked systems, and certainly the most bearable one…”

THE PRESENCE OF MR. PEKIĆ

Of fragile health from his youth, he lived with the knowledge that would not live long so he kept rushing himself to complete as many things as he could: “There’s so little time left before 1990…” He thought faster than he could write. A whole decade after his death, with the help of the magic that is called tape recorded, the recorded voice of Pekić reveals his thoughts and himself to even those who spent decades with him, his wife, and through her to his readers too.

“Soon after my husband’s death,” Ljiljana Pekić says, “I found his tapes on which he recorded ideas for his future books. I listened to them for the first time then… I had the impression that Pekić was retelling me a story over the phone what he was doing, what problems tortured him while he was writing…“ Then came new pages, new volumes of books containing diary entries, notes, and correspondence. She paid yet another tribute to Borislav Pekić when she submitted a rehabilitation request to the democratic authorities, which the court adopted in 2007.

“I think that to be a gentleman one first of all needs to be generous, brave, honest, modest and tolerant.” This sentence would briefly describe Borislav Pekić, but he would add that he is not tolerant, but rather well brought-up.

He approached any matter that he dealt with meticulously, whether he was writing about it or dealt with it practically, such as garden cultivation. He went to London, as I said, given his modesty, as an uneducated man to become one of our most educated writer, a true erudite. He died in London of lung cancer. The urn with his ashes was transferred to Belgrade and rests in the Alley of Deserving Citizens in the New Cemetery. On a marble plate on the wall of the columbarium there are eight digits that bound his earthly time, 1930-1992, and one word which should summarise all that during that time he dealt with – writer.

By Jovo Anđić

We thank the Pekić family on conceding the photographs and documents.

Photo credit: Vladimir Radojičić